Hernandez is one of 40 English teachers from Mexico who arrived at Dartmouth on Sunday morning for the Inter-American Partnership for Education Teachers' Collaborative, a program that offers 12 days of intensive instruction aimed at helping attendees become more effective English teachers, according to Jim Citron '86, the director of IAPE.

"I want to be able to make a difference for these students," Hernandez said. "I want to gain tools that I can use to really engage them with the English language and engage them in learning."

Since the summer of 2007, Dartmouth's Rassias Center for World Language and Culture has partnered with the non-profit organization Worldfund to organize the program, according to Citron. The Mexican firm Nextel de Mexico and the non-profit organization Becalos sponsor the initiative, he said.

The teachers attend daily lectures, seminars, networking programs, drill sessions and various other interactive workshops, according to Citron.

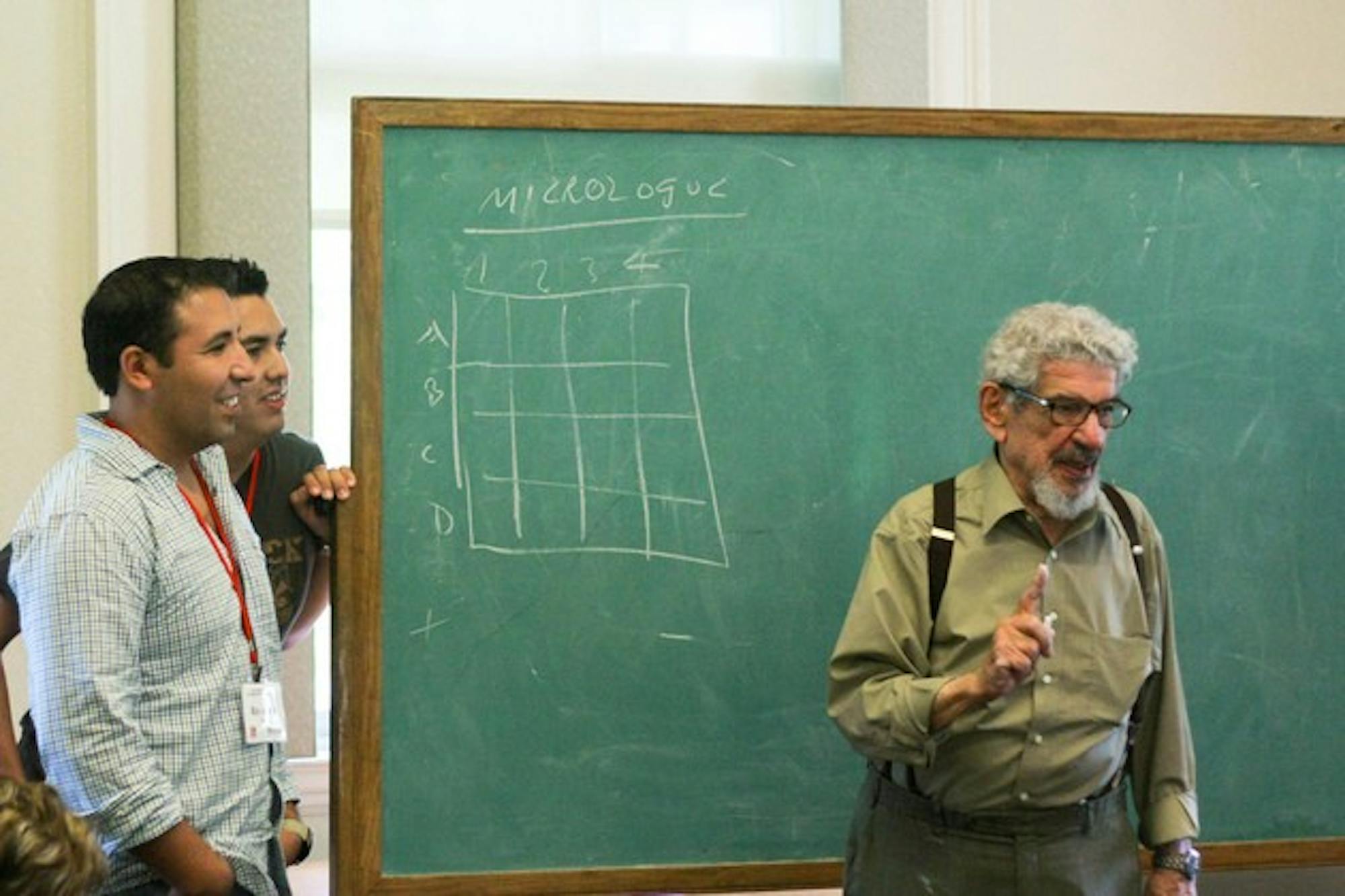

John Rassias, president of the Rassias Foundation and developer of the Rassias language method, said he will spend hours each day instructing the Mexican educators.

"Each day it's four hours with me of blood, sweat and tears," he said. "It's extremely intensive, they're not here to sit there quietly, they're here to really learn something valuable."

When Rassias called for five volunteers in a Monday afternoon workshop, almost 20 individuals stood up immediately, eager to participate.

"What makes learning work?" Rassias asked the room full of teachers. "The answer is three simple things: rhythm, emotion and movement. If you don't have these, the classroom dies."

Citron said the program is designed to help the teachers realize their full potential, ultimately creating a lasting change in Mexico's educational system.

"It's really about empowerment, which is especially important since many of them work with some of the least-resourced populations in Mexico," he said.

Jannette Carrion, who teaches a university program in Tapachula, Mexico for future teachers, said that she will pass on the techniques she learns during the program to her students, who will then be able to share them with others.

Several Mexican states that have sent teachers to Dartmouth in past years have adopted aspects of the Rassias Method for their English programs, and the State Secretary of Education of Sinaloa plans to visit Hanover next week in order to learn how to best implement such polices in Mexico, Citron said.

Blanca Josefina, who teaches at a Mexican elementary school, said that she is excited for an opportunity to improve her teaching skills.

"I love my job, but I want to become better as a professional," she said. "Sometimes I know that I don't have all the right techniques and my expectation in coming here for this program is that I will be able to learn knowledge that I can directly transmit in my classroom."

Over 130 teachers applied for the 40 spots available, Citron said.

Rassias said that teachers were chosen for the program because of their expertise.

"These aren't just any teachers," Rassias said. "We look for teachers who can and will make a difference."

Citron said that the group has demonstrated its belief in the future of Mexico and in "the power of a teacher to truly make a difference."

"There's definitely a sense of camaraderie amongst the group, part of which stems from the sense of prestige and honor that comes with being selected to the program," he said. "They feel responsible to their schools, their fellow teachers, their families, their students and to everyone back home to make the most of their time here."

Hernandez said that the group of teachers is unique in that they are all dedicated to their jobs and want to improve during the program.

"If I am surrounded by the best, I know that personally I will demand the best from myself," she said.

Hanover's IAPE program occurs "concurrently" and "synergistically" with the IAPE Intensive English Program in Mexico, Helene Rassias-Miles, executive director of the Rassias Center, said.

The Mexico-based program targets a separate group of teachers, many of whom have a lower English proficiency level than those in Hanover, Citron said. This year the Rassias Center has expanded to conducting 10 separate Mexico-based programs during the 2010-2011 school year.

"The program tries to renew enthusiasm in the teachers for their life's work," Kevin Smith '01, on-site coordinator of the IAPE program in Mexico, said. "It's wonderful to see the teachers gain confidence and leave excited to go back to their schools and apply what they've learned."

The two programs are "marvelously intertwined," in that multiple teachers who attend the Hanover program are selected to serve as teaching assistants in Mexico, Rassias-Miles said.

"The fact that some of these individuals will go back to Mexico and serve as [assistant teachers] is so exciting because this enables them to work with those teachers who don't yet have the same solid foundation that they have when it comes to the English language," she said. "It really adds a whole other mentoring dimension to the program while also making it more sustainable in the future."

An online forum set up by the program enables the teachers to stay in touch and share experiences and advice upon returning to Mexico, according to Citron.

The program was originally conceptualized by Worldfund executive director Luanne Zurlo '87, who wanted to introduce new techniques for teach English to under-resourced Mexican schools, according to Rassias-Miles.

IAPE has been recognized by the Clinton Global Initiative, a program created by former President Bill Clinton in 2005 in order to "translate practical goals into meaningful and measurable results," according to the CGIC website.