But how does this stereotype play out where it is perhaps most important: in Dartmouth's classrooms?

Several professors said that the view of the College as a conservative school is simply outdated, and noted that on the whole, the College's faculty is overwhelmingly liberal.

"A lot of our reputations of schools are based on 20 years lag time," government professor John Carey said. "When I was an undergraduate in the 80s, that was definitely Dartmouth's reputation."

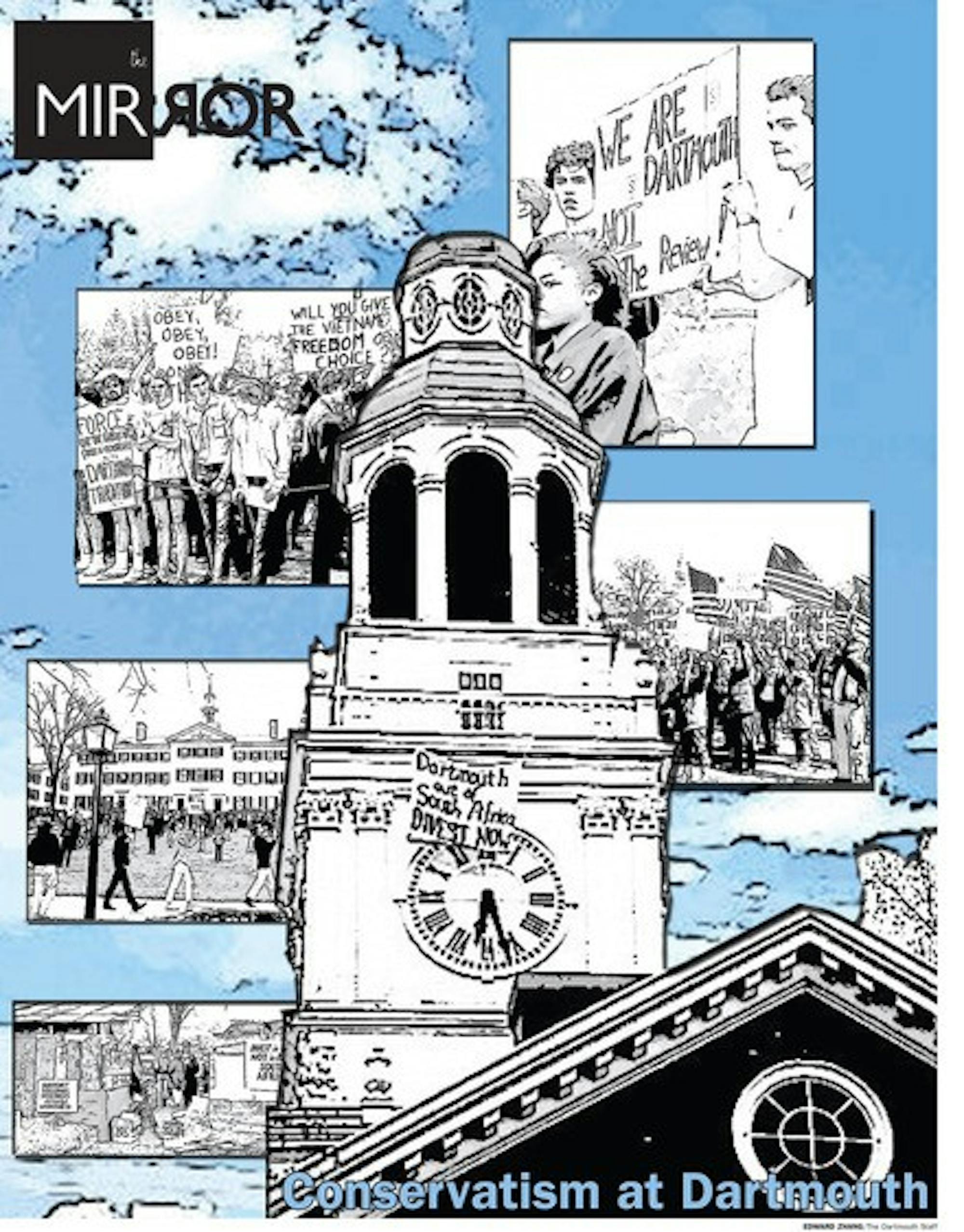

Carey said that Dartmouth was historically linked with conservatism because of events at the College surrounding highly politicized issues pointing specifically to counter-protests of students who were seeking to push Dartmouth to divest from companies doing business in South Africa before the fall of Apartheid.

"This was one of those political issues that, in retrospect it's hard to believe there was any division on it," Carey said. "So the idea that there would be counter-protests against anti-Apartheid protests was pretty shocking. And I think that resonated with a lot of people and sort of stuck."

Government professor Andrew Samwick agreed.

"I think when people say that [Dartmouth is the most conservative of the Ivy League schools], it goes back to a time when people affiliated with, say, The Dartmouth Review were very active politically and many of those alums are prominent voices in conservative circles today," Samwick said. "I simply haven't seen in my time here conservatives like they were described, so I suspect if it was [conservative] at some time, that's faded."

Even if we assume, however, that Dartmouth is somehow more conservative than its peers which it appears is a debatable point how do the College's political leanings play out for its professors and students? "There's an ongoing debate in the literature on higher education and the journalism on higher education as a whole [about professors referencing their own political stances]," Carey said. "Every once and a while you hear about these egregious cases, but I've never come across that here."

Not all professors agree on is whether personal political views should be exposed to students.

"I try to keep [politics] out [of the classroom], although I do respect faculty who do choose to talk about their political beliefs in class, as long as they're open about it," government professor Benjamin Valentino said. "The flip side of that is when you tell someone your political beliefs, some students might then discount things you say. But in general, my philosophy is that I have to trust my students to be mature enough to evaluate arguments and evidence regardless of the political views of the source, as long as it's a reasonable person."

Other professors, including Samwick, who said he is more conservative than some of his peers, are of the belief that disclosing political beliefs is the best way to ensure students aren't confusing opinion with fact.

"If I'm the least bit concerned that a student might not be able to tell when I'm speaking about something that reflects my views, some of which are informed by politics or ideology, I simply disclose it in class," he said. "Most professors are quite mindful. They would not want to be accused of bringing in their opinions where fact is appropriate."

Most professors mentioned that, while professors have every right to share their political views with students, the classroom is not a place to preach politics.

"I've thought very long and hard about the question of politics in the classroom," economics professor Meir Kohn said. "And as a rule, I don't think it's proper for professors to treat their position as a political stage."

The question for many professors is: are students of a minority political view able to comfortably present their opinions in a classroom setting?

"I think that would be one of the dangers of teaching a course and making a clear [political] stance. It's quite possible that a student would feel constrained" government professor William Wohlforth said.

The fear of voicing a minority opinion extends far beyond a fear of disagreement, Kohn said, because a mere political stance can be interpreted as a personal affront.

"I think there is a considerable amount of liberal political correctness," Kohn said. "I think someone who might object to affirmative action, for instance, [or] somebody who might have different views of President Bush than the general view that he wasn't Hitler or a monkey might feel more reluctant to express themselves [considering the liberal atmosphere]."