The University Press of New England board of governors voted on Apr. 17 to dissolve the publishing consortium and wind down operations by December. Founded in 1970, the UPNE consortium included as many as 10 institutions, but for the last two years, it has been run by Dartmouth and Brandeis University. Both institutions indicated that the decrease in membership over the years made the press “financially unsustainable” to operate and that they will take independent control of their own imprints.

College spokesperson Diana Lawrence wrote in an email statement that the increase in financial support from the College for UPNE without any “commensurate increase in production volume for the remaining member imprints” presents a significant liability. UPNE has sales under $1.5 million annually and the costs are offset by sales, services provided to other publishers, title subsides or grants from authors and member support, Lawrence wrote.

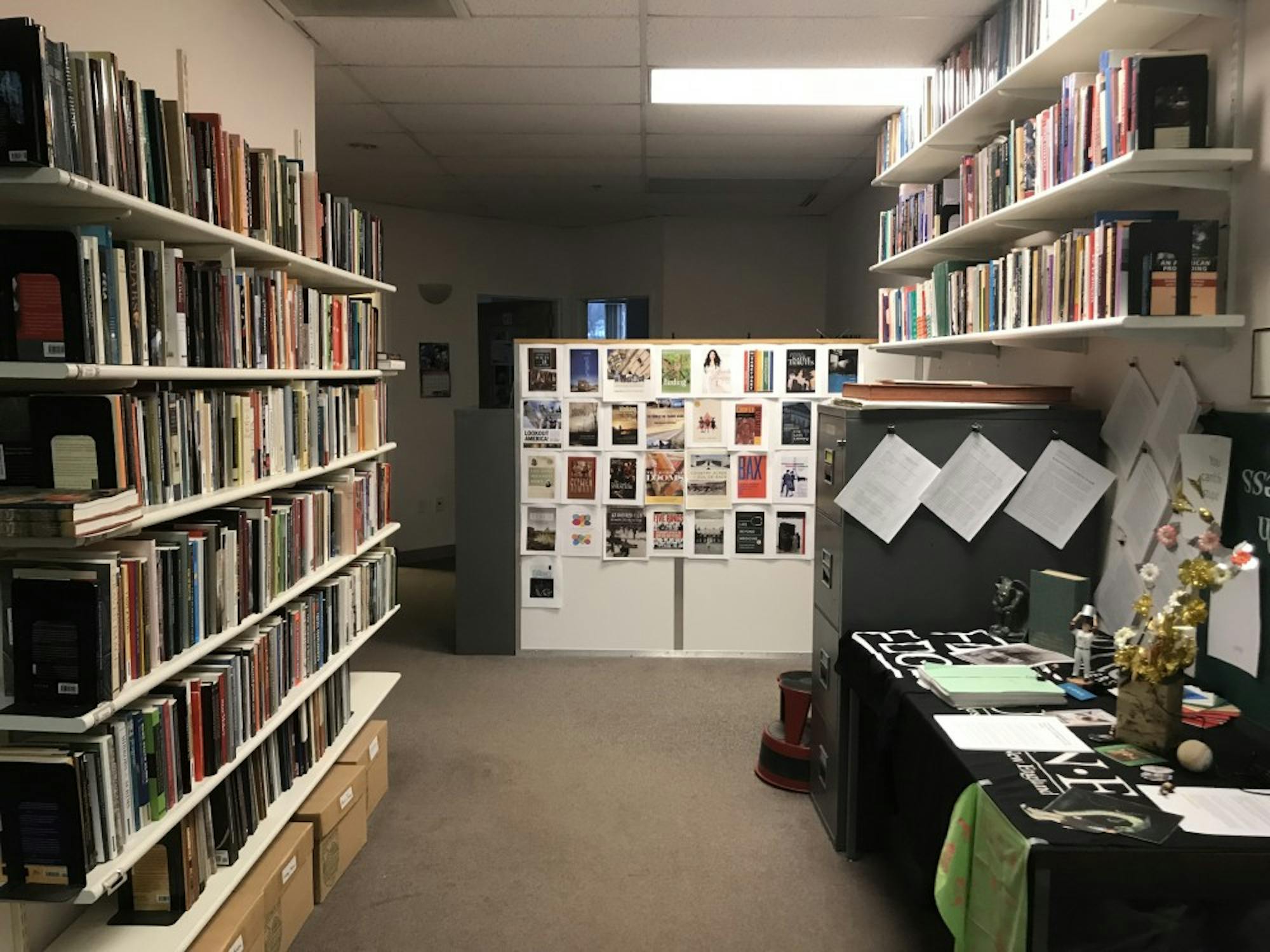

As the host institution, the College employs all of UPNE’s 20 staff members, and the press is headquartered in Lebanon, New Hampshire. UPNE production coordinator Doug Tifft said that the press also depends on freelancers for production editing, design and typesetting. The College has scheduled individual appointments for UPNE staff members with Dartmouth College Human Resources to assist them with the transition, according to Tifft.

“[Dartmouth] will take care of people both in terms of giving them a certain amount of severance and putting them in touch with job placement groups,” Tiff said. “I have no complaints so far in how they have treated us since they made their decision.”

Former editor-in-chief of the UPNE Phyllis Deutsch said that state wide budget cuts for public universities prompted the universities to leave the consortium over the years.

She added that the expense of membership fees did not seem to balance the benefits these institutions received by being a part of the consortium in terms of prestige and status. As institutions left the consortium, costs increased for remaining members, Deutsch explained.

“Every time [an institution] dropped out, the membership costs were split among fewer members, so [the costs] went up,” she said. “It became a recurring pattern.”

UPNE also felt the effects of shifting trends in academic publications, according to Deutsch. For example, university presses previously published monographs, which covered broad new topics such as women’s studies and African-American studies. With the increase in graduate students, however, these monographs became narrower and geared towards smaller audiences, selling fewer copies. This decrease in popularity of monographs since they were first published in the 1960s could explain the decrease in sales, Deutsch said.

Acquisitions editor of the UPNE Stephen Hull added that due to the limited sales of scholarly monographs, in 2014, UPNE launched ForeEdge, a specialized trade name or imprint, to publish general interest books for a wider national audience.

“With [institutions] of higher education turning out more graduate students, the books started getting narrower, more theoretical and were increasingly written for a small [audience],” Deutsch said. “There weren’t as many reasons to buy the books unless they were exactly in your field.”

UPNE’s publishing program focuses on the humanities, arts, literature, New England culture and interdisciplinary studies. Some notable publications include winner of the 2004 National Book Award in Poetry, “Door in the Mountain,” by Jean Valentine and winner of the 1994 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry “Neon Vernacular: New and Selected Poems” by Yusef Komunyakaa.

In fiscal year 2017, UPNE published 60 titles, which included 21 member titles that carry a joint imprint and 39 titles under the UPNE imprint. Of the 21 member titles, the Dartmouth College Press published eight books while Brandeis University Press published 13. UPNE also distributes around 140 titles annually from small to medium-sized publishers through its Book Partners program, according to the UPNE website.

History and Native American studies professor Colin Calloway said that the closure of the press is a loss, but recognizes that at the same time the press is less robust than when he first worked with them in the 1990s.

“I don’t know enough [about the financial considerations] to say that this is a huge mistake … hopefully it took a lot of careful consideration,” Calloway said. “At the same time, not everything should be about the financial considerations, and university presses are not typically money-making operations.”

Tifft said that the shutdown of the press is a blow to non-profit book publishing because scholars now have one less place to publish their academic work.

“Profit doesn’t measure value when it comes to [evaluating] the worth of a book,” Tifft said. “Profit was based on how many people might buy [the book], but it doesn’t measure how long it will be around … and how many people will read one [sole] copy.”

Hull said that his first concern is taking care of both the authors that had their books recently published and authors with titles under contract that will no longer be published by the press.

The College has commissioned a faculty study group, led by professor Graziella Parati, that is charged with evaluating the future of the Dartmouth College Press, which used to be a part of the UPNE consortium. The study group will present their recommendations to the president and provost of the College in November.