With intense political discourse persisting well beyond this past election, The Dartmouth set out to examine the contours of Dartmouth student public opinion regarding current events. In a campus-wide survey fielded from April 9 to April 13, 432 students answered questions about several issues, such as tolerance for and relations with opposing political viewpoints, views toward President Donald Trump and recent government actions like the Syrian missile strike earlier this month. The findings speak to contemporary debates and provide an understanding of where students stand on current political issues.

Among all respondents, 63 percent identified as Democrat, 23 percent as Republican and 14 percent as independent.

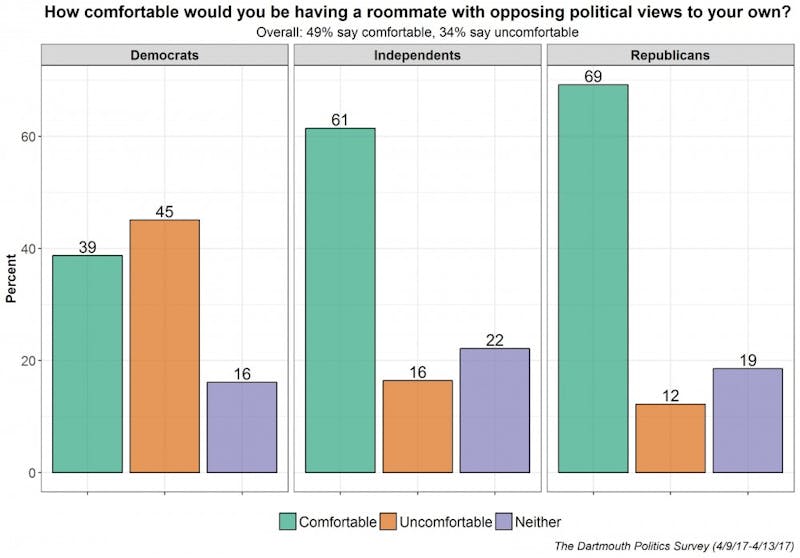

Interpersonal political relations have increasingly gained attention on college campuses. One way to get a sense of this dynamic is to assess comfort levels among college students when interacting with others of opposing ideologies. When students at the College were asked how comfortable they would be having a roommate with opposing political views to their own, 49 percent said they would be very or somewhat comfortable, whereas 34 percent said they were very or somewhat uncomfortable.

This sentiment of openness to politically divergent roommates was not equally distributed across students of different political stripes. While 61 percent of independents and 69 percent of Republicans said they would be comfortable with a roommate of opposing political views, only 39 percent of Democrats said so. Few independents (16 percent) and Republicans (12 percent) said they would be uncomfortable. Because of small sample size issues, the difference between the percentage of Democrats who said they were comfortable and the percentage who said uncomfortable was not statistically significant.

President of Dartmouth College Democrats Charlie Blatt ’18 said she was not surprised that most Republicans reported they were comfortable with having a Democratic roommate, given that a majority of students at the College are Democrats.

“It’s unfortunate — I wish we had more political diversity,” she said. “I think the dialogue is good.”

Vice president of the Dartmouth College Republicans Abraham Herrera ’18 echoed Blatt’s sentiment, saying that since Republicans are a minority on campus, they will end up with a roommate of opposing political views the majority of the time.

Herrera said he was surprised by the large number of Republicans and the lack of Democrats that were comfortable with an out-party roommate.

If anything, managing editor of the Dartmouth Political Times Sydney Walter ’18 said she would have expected a greater divide in the potential discomfort between Republicans and Democrats.

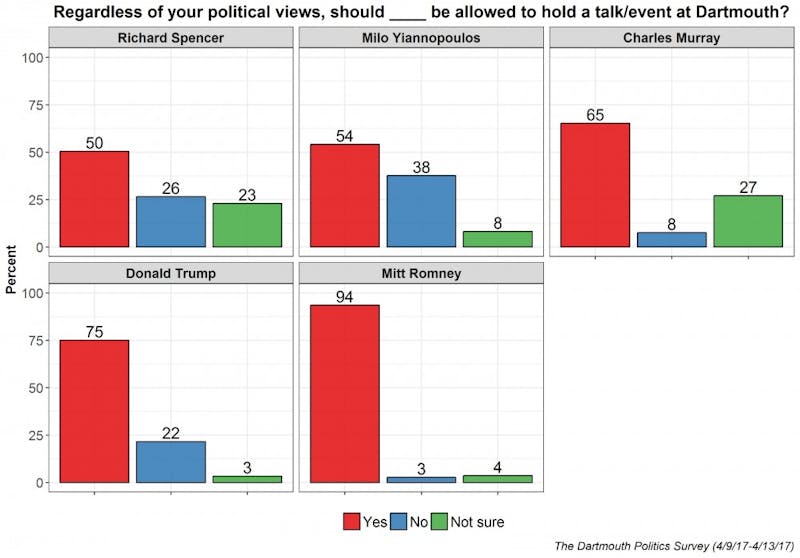

Many of the claims about political intolerance on college campuses have stemmed from student reactions to invited speakers who tend to espouse conservative ideology and rhetoric. To speak to this issue, Dartmouth students were asked whether, regardless of their own political views, they thought certain figures from the political right should be allowed to hold a talk or event at Dartmouth. The set of figures was chosen to create a mainstream-extreme right-wing spectrum: former Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, conservative author Charles Murray, Trump, alt-right personality Milo Yiannopoulos and white nationalist Richard Spencer.

For almost every speaker, a majority of students said they should be allowed to speak at the College: 94 percent said yes for Romney, 75 percent for Trump, 65 percent for Murray, 54 percent for Yiannopoulos and 50 percent for Spencer. The greatest opposition came for Yiannopoulos, with 38 percent saying he should not be able to speak at the College, but nonetheless many more students said he should be allowed.

Breaking up the same results by party revealed Democrats as being more reluctant to say some of these speakers should be allowed to give a talk. Namely, more Democrats said no to Yiannopoulos — 38 percent yes, 52 percent no — and Democrats were about equally divided on Spencer — 35 percent each saying yes and no, while 30 percent were unsure or unfamiliar. For Murray, 54 percent of Democrats were okay with him holding an event at Dartmouth while 10 percent were not okay. On the other end, Republicans were overwhelmingly okay with allowing every speaker listed — Spencer was the lowest on the list, but even then, 83 percent of Republicans said he should be allowed to speak at Dartmouth.

Different students emphasized the importance of hearing dissenting opinions and commented on the nature of political tolerance at the College. Walter said she expected more people to have been against Yiannopoulos as a speaker.

Blatt said that she was surprised there was not more “uproar” when Yiannopoulos visited campus this last November. She also said she “falls under the school of thought that more speech is good speech,” and response to speech with which one disagrees is still more speech.

“I vehemently disagree with everything Milo Yiannopoulos stands for, but that does not mean I [think] we shouldn’t have him on this campus because I think we should have him here to challenge his views,” she said.

Based on the protests over Emily Yoffe, a speaker from October 2015 who held controversial views regarding campus sexual assault, Herrera said that he does not think that all Dartmouth students have the same opinion that all discourse is good.

He added that he does not consider Charles Murray to be “that problematic” as a speaker since he brings discourse based on research.

“I think some of the points that he makes may seem [uncomfortable] at first, but he does research and he’s a scholar on these issues so he doesn’t bring a biased perspective in my opinion,” Herrera said.

The publicity surrounding Charles Murray at Middlebury College, where students violently protested his talk, may have convinced Dartmouth students that such speakers should not be brought to campus because it was “so rough” on Middlebury, Blatt said. She added that the term “controversial” at the College is now often thought of as “probably right-leaning” since the balance of political opinions is left-leaning.

Walter added that students in the middle of the political spectrum are not as politically engaged and visible, which is reflective of the rest of the country.

“We only really tend to hear from people from either ends of the spectrum,” Walter said.

When she works with conservative students in writing for the Dartmouth Political Times, Walter said they feel uncomfortable voicing their opinion in fear that they will experience backlash.

“I think they feel that if they voice something that’s even a well-educated and well-founded opinion, just because it might come from a conservative stint, people will refuse to hear it,” she said.

Blatt said she would be curious to see how Republicans at the College would feel about a controversial liberal speaker such as Cecile Richards, the president of Planned Parenthood.

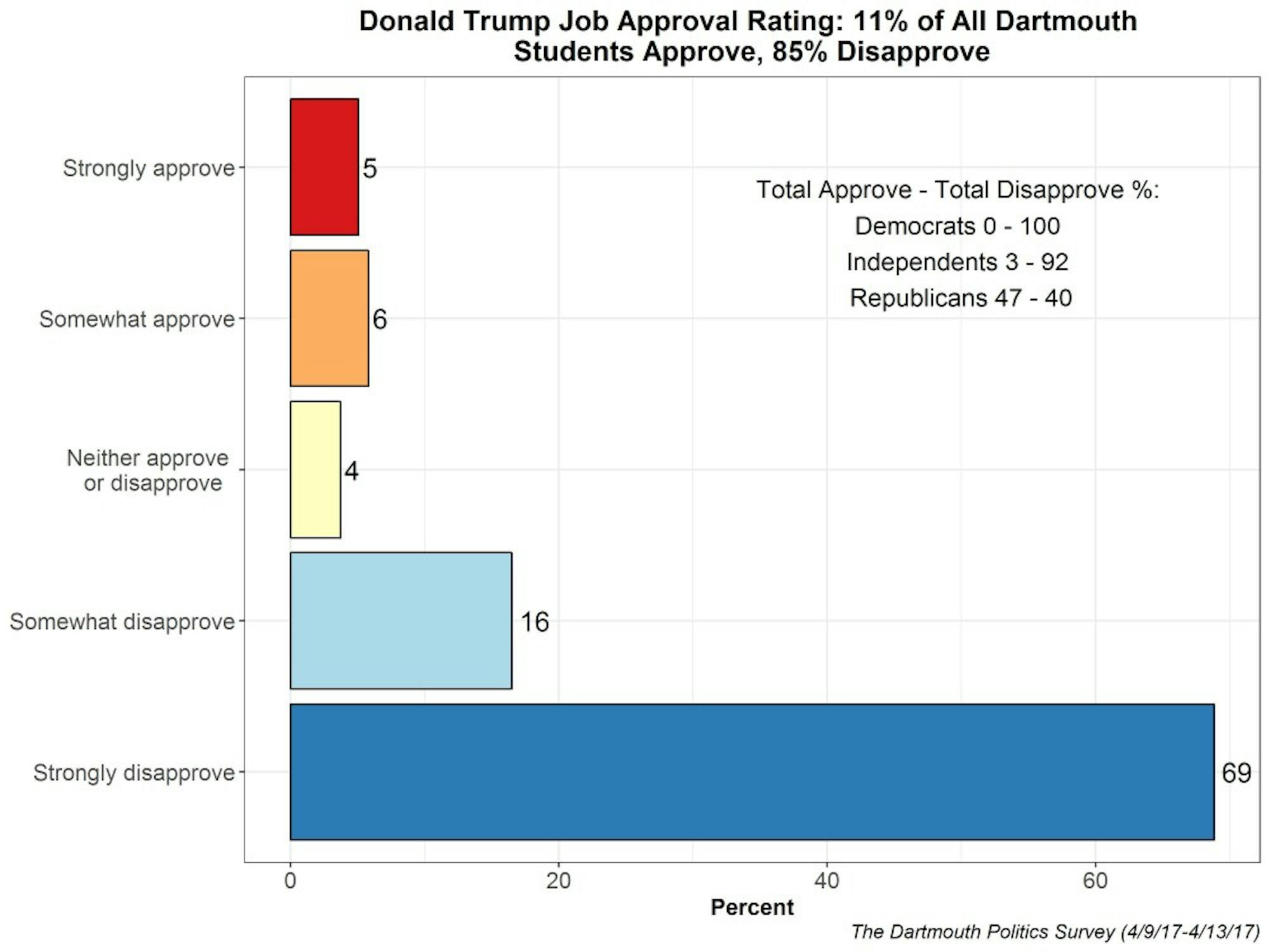

Popular political accounts of the College’s student body often portray a staunchly left-leaning campus. Public opinion data backs this up well, and so it is no surprise that a Republican like Trump receives poor approval ratings from students on campus. When asked whether they approved or disapproved of the way Trump is handling his job as president, 11 percent of students said they strongly or somewhat approved, while 85 percent said they strongly or somewhat disapproved. Interestingly, the disapproval percentage exactly matches the percentage of students who intended to vote for former Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton when The Dartmouth polled about voting choice in the run-up to the 2016 general election. This might imply that students initially against Trump continue to be so, unchanged by the election result, inauguration or the first few months of the Trump presidency.

Gauging student opinion on Trump among different partisanship identities adds another layer of understanding. Democrats are resolutely against the president, as just under 100 percent of them say they disapprove.

Independents who do not lean toward any party hold similar levels of distaste: only 3 percent approve of Trump, compared to 92 percent who disapprove. Republicans, on the other hand, are much more split: 47 percent approve of Trump and 40 percent disapprove. Because of a small sample size, that different is not significant, but the result does imply that roughly equal numbers of Republicans on campus approve and disapprove of the president from their own party.

Blatt said people usually have a strong instinct to defend the political candidate or party that lines up with their ideology, even when confronted with contradictory information.

Given the relatively high level of education of the student body, Blatt said it is interesting that students at the College align with what political research says about party affiliation and loyalty.

“You’d think that if anyone was going to change their opinion about a president, it would be this group of people,” Blatt said.

Walter said the results play into the narrative that Trump supporters have a low bar for support given the style of his presidential campaign.

“I think he demonstrated the full gambit of who he is from the election, and if they were still willing to vote for him, I’d be shocked now if they decided to turn away,” she said.

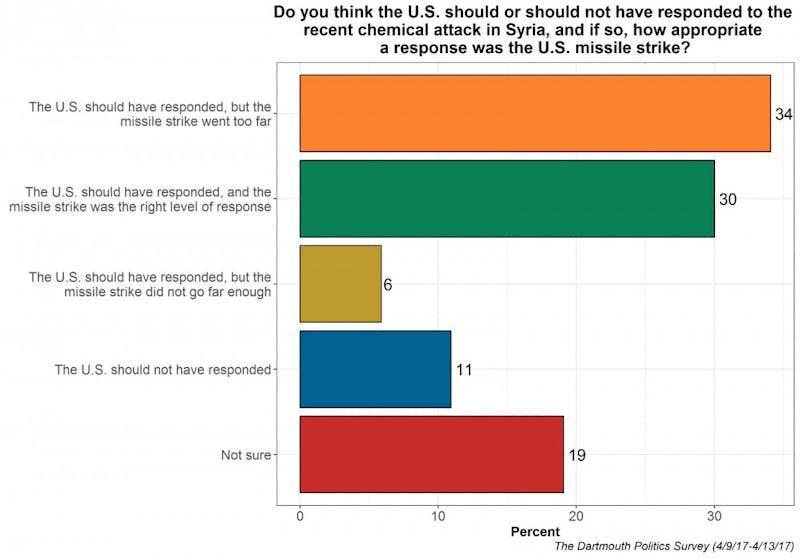

At the time of the survey’s administration, a very topical issue was the recent chemical attack in Syria and Trump’s response in the form of a missile strike. Students were asked whether or not the U.S. should have responded to the chemical attack and how appropriate a response was a missile strike. Only 11 percent of Dartmouth students said the U.S. should not have responded at all, while 70 percent said it should have responded in some way. Within this 70 percent who thought a response was necessitated, 34 percent said the U.S. should have responded but it went too far, and 30 percent said that the U.S. should have responded and the missile strike was the right level of response. Only 6 percent said they approved of a response but did not think the missile strike went far enough.

Democratic, Republican and independent students were about as equally likely to say that the U.S. should have responded in some way. However, 42 percent of Democrats said that the missile strikes went too far, while 59 percent of Republicans viewed the strikes as the right level of response.

Blatt said that even as a staunch Democrat and someone who studies international relations, she has a difficult time figuring out what is the best course of action. Thus, she was not surprised by the wide range of responses to the question.

Under the foreign policy of former President Barack Obama’s administration, the United States refused to use military retaliation with Syria but reserved chemical weapons as a “red line.” However, when evidence of chemical weapons was found, the Obama administration opted to negotiate a deal with Russia and Syria with the promise that Russia would supervise the removal of all chemical weapons.

Walter said there was a lot of conservative frustration over these policies and said this was a clear example of Obama not following through on his own policy. The rationale was that there would be no way to prevent becoming further involved with Syria, Blatt said.

Walter pointed out that there could be a knowledge gap on the conflict. In other words, if a student is interested they will know a lot about the issue, but otherwise it is more of a “headline thing.”

“[The results] are close enough, in my opinion, that people are just like ‘He responded and what would my ideological leaning tell me about this,’” she said.

The “yes-side” indicates the excusability of chemical weapons, while the “no-side” represents an unwillingness to become further involved with Syria in a slippery slope, Blatt said. Herrera agreed that Syria has become a contentious issue with both Democrats and Republicans opposing and supporting the strikes.

Democrats, in general, likely responded more positively to the strikes since it seemed to be the first “presidential” action Trump had taken without any scandal or mishap, Walter said.

“It was a strong step that showed leadership,” Walter said.

Now while there is conservative support of Trump taking action in Syria, many more Americans are “war-weary” or not interventionists, Walter said.

“The United States is going through a little bit more isolationist nationalist rise that we’re seeing across Europe as well and led to the Trump presidency,” she said.

Herrera said he considers himself a “neo-conservative” when it comes to foreign policy in that he thought the response was at the right level and that the U.S ought to become more involved with Syria.

He also added there may be an element of “political expediency” or that public opinion has shifted on how aggressive U.S foreign policy should be.

Methodology Notes:

From Sunday, April 9 to Thursday, April 13, The Dartmouth fielded an online survey of Dartmouth students on community-related topics. The survey was sent out to 4,200 students through their school email addresses. 432 responses were recorded, making for a 10.3 percent response rate. Using administrative data from the College’s Office of Institutional Research, responses were first weighted by Greek affiliation for all non-freshmen, and then weighted by class year, gender, race/ethnicity and international student status for all students. Iterative post-stratification (raking) was the method used for weighting. Survey results for all respondents have a margin of error of +/- 4.8.

Note: Only differences within a demographic that were statistically significant are reported.

Correction Appended (May 4, 2017):

A previous version of this article stated that "statistically Democrats were as likely to say they would be comfortable as they would be uncomfortable [with a roommate of opposing political views]." To clarify the language and better reflect the statistical test used, the article was updated to read, "Because of small sample size issues, the difference between the percentage of Democrats who said they were comfortable and the percentage who said uncomfortable was not statistically significant."

Correction Appended (Nov. 28, 2017):

Methodology notes for the previous version of the April 26, 2017 article “A survey of Dartmouth's political landscape” stated that the survey was an “opt-in” one and reported a “credibility interval.” Because every student in our target population is contacted to take the survey, these terms are incorrect and the methodology notes have been updated accordingly.

Amanda Zhou is a junior at Dartmouth College originally from Brookline, Massachusetts. She’s previously been the associate managing editor, health and wellness beat writer at the Dartmouth and interned at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette this Fall. She is pursuing a major in quantitative social science and a minor in public policy. At college, she edits the campus newspaper, serves on the campus EMS squad and lives in the sustainable living center. After graduation, she is interested in a career in journalism or data analysis. In her spare time, she can be found running, cooking or trying to rock climb.