The College is finalizing proposals to convert to a hot water heating system and biomass energy system from the current oil system and steam distribution system. These proposed changes would upgrade the College’s steam distribution system and cogeneration plant to increase both efficiency and sustainability, said Frank Roberts, associate vice president of facilities operations and management.

Currently, electricity and heat on campus originate from the College’s cogeneration plant. The plant produces steam by burning No. 6 oil, driving a turbine that produces electricity, Roberts said. The remainder of the steam is used to heat buildings. The majority of older buildings on campus rely on this method for heat while newer or renovated buildings use hot water or a mixture of water and steam.

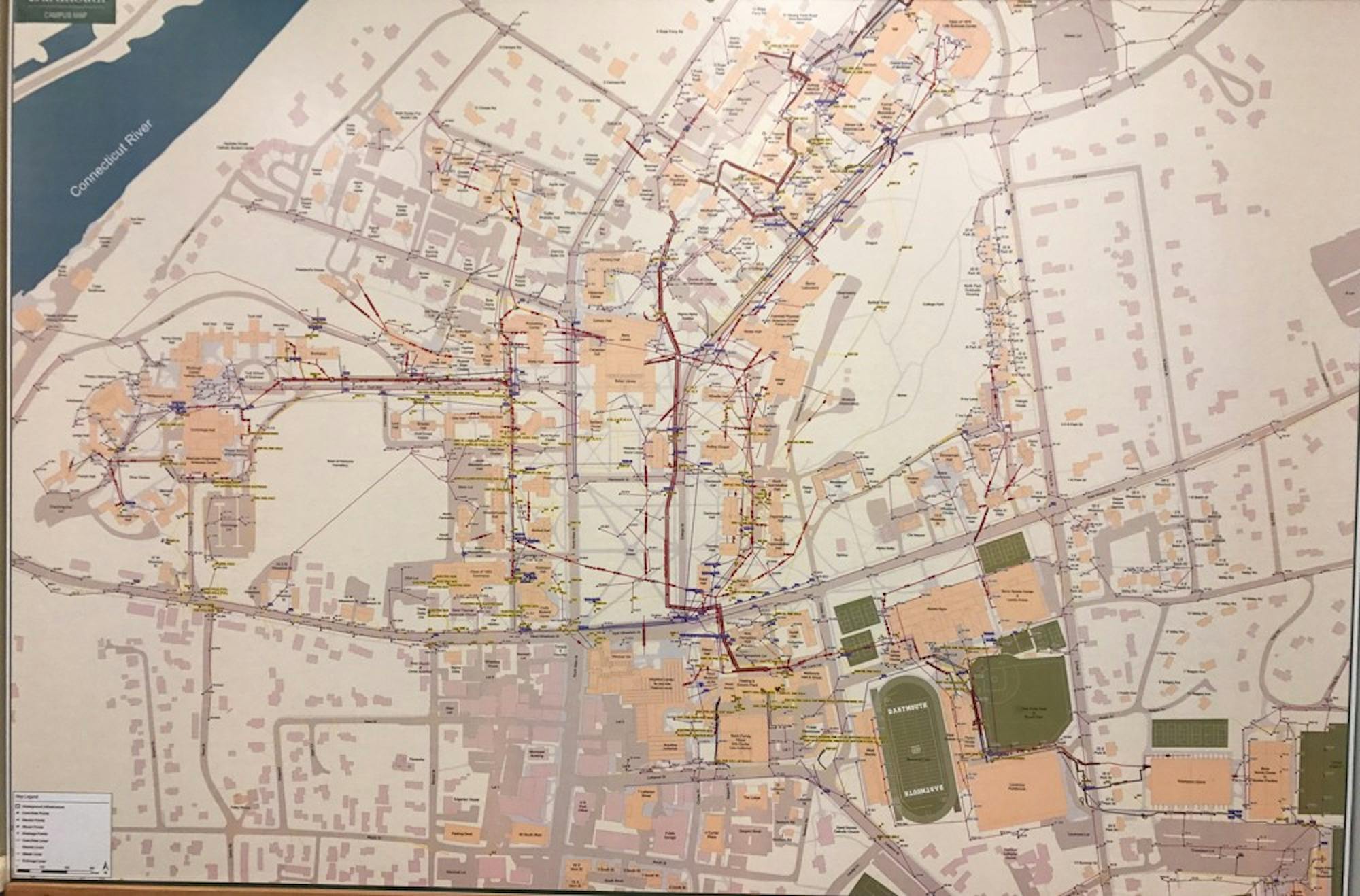

The cogeneration plant burns 3.8 million gallons of environmentally harmful No. 6 oil per year. While economically efficient, the use of this oil gives Dartmouth the largest carbon footprint per student in the Ivy League. Furthermore, the College’s steam distribution system is aging and will soon require repairs or replacement, Roberts said. Many steam lines, such as the line that runs under the south side of the Green, lack proper insulation and lose energy during transportation. Twenty percent of lines have not been replaced in 65 to 75 years.

In order to examine ways to possibly improve the system, the College began an analysis of the efficiency of a biomass and hot water system alternative in November 2015. The analysis cost the College $550,000, Roberts said, but the results have not been finalized. FO&M is also working with the Dartmouth Sustainability Project and outside consultants to determine the feasibility of the transition.

“We have to spend money and upgrade the infrastructure for the steam distribution system,” Roberts said. “If you take that money, invest it in a new hot water system, convert your buildings to hot water, as well as change over to biomass as a renewable resource and get off [No. 6 oil], there are labor savings, other operation savings and fuel savings.”

The use of a hot water system could increase the efficiency of the College’s heating system by 20 percent, he added. While the Life Sciences Center is three times larger than the currently unused Gilman Life Sciences Laboratory, it uses 10 times less energy because it uses a hot water system instead of a steam system, Roberts said.

Member of Divest Dartmouth Ches Gundrum ’17 said that the benefits of transitioning to a more environmentally conscious system goes beyond reducing costs.

“If the College were to divest, they would immediately send a statement that this college cares about its students, its future students and future students beyond that,” she said.

While this proposal is nearly complete, the entire process is still in very early stages, Diana Lawrence, spokesperson for the College, wrote in an email statement. Estimated costs for the hot water system alone could total more than $100 million, and the combined cost of converting to a biomass and hot water system could range from $250 to $300 million, according to Roberts.

“The expected return [on the transition] is highly variable based on assumptions about the timing of the implementation of the project,” Lawrence wrote. “It requires a thorough analysis, as the choice to invest in this project will need to be prioritized with other Dartmouth initiatives requiring investment.”