As the first hints of a Southern autumn began to creep onto the glimpses of burnt oranges and overcast grays, Emory University saw its campus flourish in a sea of blue. When the university’s student government executive board urged individuals to wear blue on Oct. 6, the initiative blossomed throughout campus. Blue bed sheets hung from windows, and several Emory students passed out free shirts they had spent the previous night stenciling by hand. Greek organizations soon took the charge — several fraternities covered their windows in blue crepe paper, and sororities painted their windows blue, with messages of support across them. “We stand together,” read one window, its blue and white color scheme accentuating the Star of David in the center of a heart.

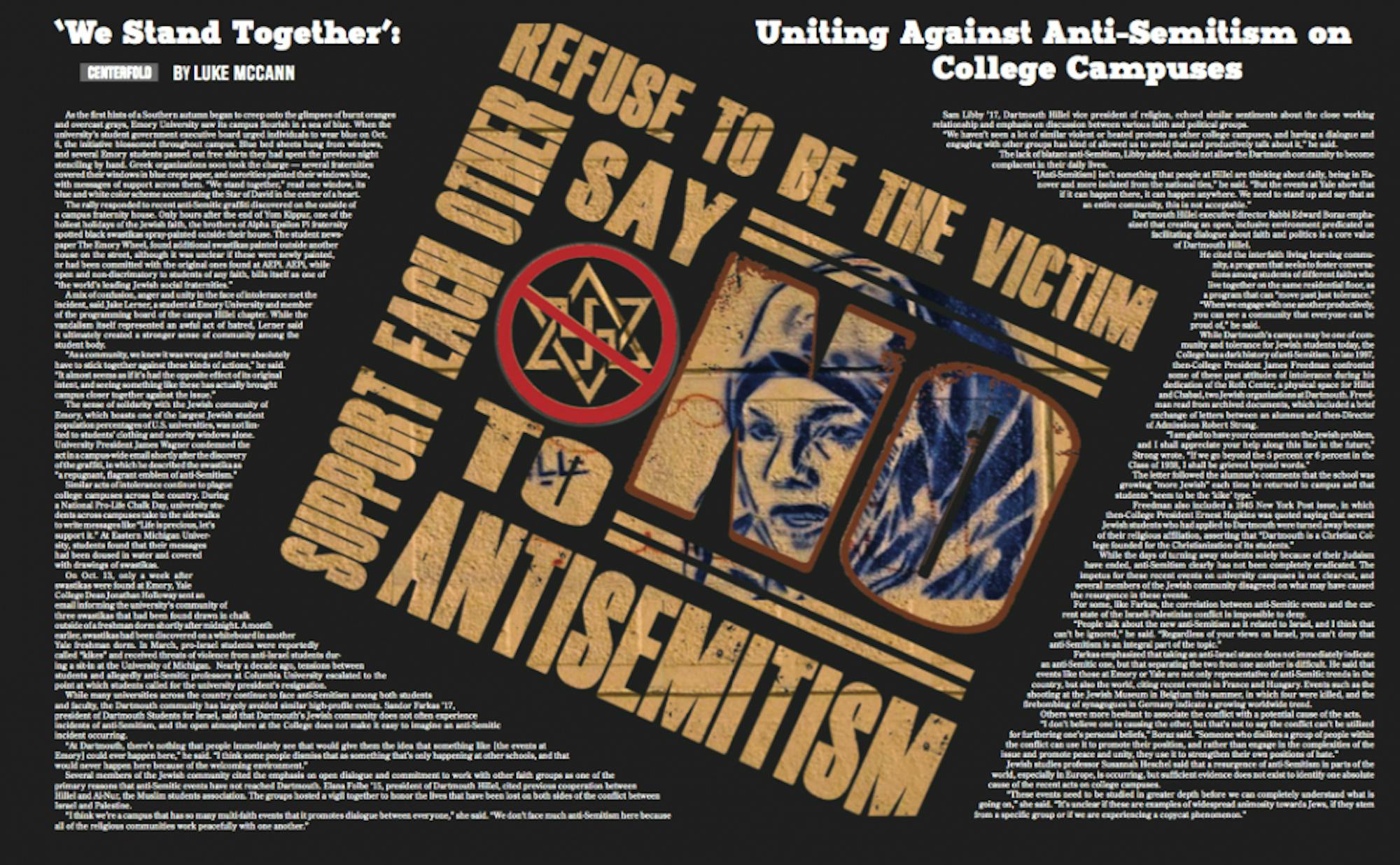

The rally responded to recent anti-Semitic graffiti discovered on the outside of a campus fraternity house. Only hours after the end of Yom Kippur, one of the holiest holidays of the Jewish faith, the brothers of Alpha Epsilon Pi fraternity spotted black swastikas spray-painted outside their house. The student newspaper The Emory Wheel found additional swastikas painted outside another house on the street, although it was unclear if these were newly painted, or had been committed with the original ones found at AEPi. AEPi, while open and non-discrimatory to students of any faith, bills itself as one of “the world’s leading Jewish social fraternities.”

A mix of confusion, anger and unity in the face of intolerance met the incident, said Jake Lerner, a student at Emory University and member of the programming board of the campus Hillel chapter. While the vandalism itself represented an awful act of hatred, Lerner said it ultimately created a stronger sense of community among the student body.

“As a community, we knew it was wrong and that we absolutely have to stick together against these kinds of actions,” he said. “It almost seems as if it’s had the opposite effect of its original intent, and seeing something like these has actually brought campus closer together against the issue.”

The sense of solidarity with the Jewish community of Emory, which boasts one of the largest Jewish student population percentages of U.S. universities, was not limited to students’ clothing and sorority windows alone. University President James Wagner condemned the act in a campus-wide email shortly after the discovery of the graffiti, in which he described the swastika as “a repugnant, flagrant emblem of anti-Semitism.”

Similar acts of intolerance continue to plague college campuses across the country. During a National Pro-Life Chalk Day, university students across campuses take to the sidewalks to write messages like “Life is precious, let’s support it.” At Eastern Michigan University, students found that their messages had been doused in water and covered with drawings of swastikas.

On Oct. 13, only a week after swastikas were found at Emory, Yale College Dean Jonathan Holloway sent an email informing the university’s community of three swastikas that had been found drawn in chalk outside of a freshman dorm shortly after midnight. A month earlier, swastikas had been discovered on a whiteboard in another Yale freshman dorm. In March, pro-Israel students were reportedly called “kikes” and received threats of violence from anti-Israel students during a sit-in at the University of Michigan. Nearly a decade ago, tensions between students and allegedly anti-Semitic professors at Columbia University escalated to the point at which students called for the university president’s resignation.

While many universities across the country continue to face anti-Semitism among both students and faculty, the Dartmouth community has largely avoided similar high-profile events. Sandor Farkas ’17, president of Dartmouth Students for Israel, said that Dartmouth’s Jewish community does not often experience incidents of anti-Semitism, and the open atmosphere at the College does not make it easy to imagine an anti-Semitic incident occurring.

“At Dartmouth, there’s nothing that people immediately see that would give them the idea that something like [the events at Emory] could ever happen here,” he said. “I think some people dismiss that as something that’s only happening at other schools, and that would never happen here because of the welcoming environment.”

Several members of the Jewish community cited the emphasis on open dialogue and commitment to work with other faith groups as one of the primary reasons that anti-Semitic events have not reached Dartmouth. Elana Folbe ’15, president of Dartmouth Hillel, cited previous cooperation between Hillel and Al-Nur, the Muslim students association. The groups hosted a vigil together to honor the lives that have been lost on both sides of the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

“I think we’re a campus that has so many multi-faith events that it promotes dialogue between everyone,” she said. “We don’t face much anti-Semitism here because all of the religious communities work peacefully with one another.”

Sam Libby ’17, Dartmouth Hillel vice president of religion, echoed similar sentiments about the close working relationship and emphasis on discussion between various faith and political groups.

“We haven’t seen a lot of similar violent or heated protests as other college campuses, and having a dialogue and engaging with other groups has kind of allowed us to avoid that and productively talk about it,” he said.

The lack of blatant anti-Semitism, Libby added, should not allow the Dartmouth community to become complacent in their daily lives.

“[Anti-Semitism] isn’t something that people at Hillel are thinking about daily, being in Hanover and more isolated from the national ties,” he said. “But the events at Yale show that if it can happen there, it can happen anywhere. We need to stand up and say that as an entire community, this is not acceptable.”

Dartmouth Hillel executive director Rabbi Edward Boraz emphasized that creating an open, inclusive environment predicated on facilitating dialogue about faith and politics is a core value of Dartmouth Hillel.

He cited the interfaith living learning community, a program that seeks to foster conversations among students of different faiths who live together on the same residential floor, as a program that can “move past just tolerance.”

“When we engage with one another productively, you can see a community that everyone can be proud of,” he said.

While Dartmouth’s campus may be one of community and tolerance for Jewish students today, the College has a dark history of anti-Semitism. In late 1997, then-College President James Freedman confronted some of these past attitudes of intolerance during his dedication of the Roth Center, a physical space for Hillel and Chabad, two Jewish organizations at Dartmouth. Freedman read from archived documents, which included a brief exchange of letters between an alumnus and then-Director of Admissions Robert Strong.

“I am glad to have your comments on the Jewish problem, and I shall appreciate your help along this line in the future,” Strong wrote. “If we go beyond the 5 percent or 6 percent in the Class of 1938, I shall be grieved beyond words.”

The letter followed the alumnus’s comments that the school was growing “more Jewish” each time he returned to campus and that students “seem to be the ‘kike’ type.”

Freedman also included a 1945 New York Post issue, in which then-College President Ernest Hopkins was quoted saying that several Jewish students who had applied to Dartmouth were turned away because of their religious affiliation, asserting that “Dartmouth is a Christian College founded for the Christianization of its students.”

While the days of turning away students solely because of their Judaism have ended, anti-Semitism clearly has not been completely eradicated. The impetus for these recent events on university campuses is not clear-cut, and several members of the Jewish community disagreed on what may have caused the resurgence in these events.

For some, like Farkas, the correlation between anti-Semitic events and the current state of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is impossible to deny.

“People talk about the new anti-Semitism as it related to Israel, and I think that can’t be ignored,” he said. “Regardless of your views on Israel, you can’t deny that anti-Semitism is an integral part of the topic.”

Farkas emphasized that taking an anti-Israel stance does not immediately indicate an anti-Semitic one, but that separating the two from one another is difficult. He said that events like those at Emory or Yale are not only representative of anti-Semitic trends in the country, but also the world, citing recent events in France and Hungary. Events such as the shooting at the Jewish Museum in Belgium this summer, in which four were killed, and the firebombing of synagogues in Germany indicate a growing worldwide trend.

Others were more hesitant to associate the conflict with a potential cause of the acts.

“I don’t believe one is causing the other, but that’s not to say the conflict can’t be utilized for furthering one’s personal beliefs,” Boraz said. “Someone who dislikes a group of people within the conflict can use it to promote their position, and rather than engage in the complexities of the issue and promote peace and unity, they use it to strengthen their own positions of hate.”

Jewish studies professor Susannah Heschel said that a resurgence of anti-Semitism in parts of the world, especially in Europe, is occurring, but sufficient evidence does not exist to identify one absolute cause of the recent acts on college campuses.

“These events need to be studied in greater depth before we can completely understand what is going on,” she said. “It’s unclear if these are examples of widespread animosity towards Jews, if they stem from a specific group or if we are experiencing a copycat phenomenon.”